- Contact Us Now: 754-400-5150 Tap Here to Call Us

Even Though She Paid, The Bank Still Tried to Take Our Client’s Home!

As detailed below, there were never any issues with this loan until a new servicer took over. At no point in time was this client unable to pay her mortgage payments. But for the bank and its debt collector/servicer, this case should never have been filed.

Our client has lived in her condominium for over 20 years. She’s had a full-time job with the same company for over 23 years, making approximately $63,000 per year. Her mortgage payment is $662.56 per month. Underwriting standards dictate that housing debt is generally affordable so long as it does not exceed 28% of a person’s income. Our client’s housing debt is 10% of her income. For many years, until the incidents leading up to this case, our client’s mortgage payments were auto debited from her checking account without issue. She had no issue affording this loan, ever.

And, she has always paid her taxes and her association dues, which includes insurance. There were no escrows.

In March of 2015, the servicing of the loan transferred. After years of timely auto debits in the correct amount, the new “servicer” auto debited $1,006.72 on March 28, 2016. (Servicer is just a fancy sounding term that banks created. They are really just “debt collectors.”) This new amount was $344.16 more than her fixed monthly payment. The servicer did not give any advance warning and our client never authorized them to take more than her fixed payment.

As revealed in the servicer’s comment log, which we obtained and admitted into evidence at trial, our client called in the day this happened. The representative advised that the increase was due to force-placed insurance. Our client stated that she already faxed over proof of insurance and that this should be adjusted as her condo carries adequate coverage. She relayed the phone number for the company that provides insurance information for the association.

The following day, our client once again faxed over proof of insurance showing coverage from June 2015 to June 2016. She also stopped all future auto debits. The evidence admitted at trial included insurance declaration sheets, proof of payments from her bank account, and numerous e-mails between our client, the condo, the insurance agents, and the servicer. This, as well as our client’s testimony, established that she was on top of this issue. She sent in proof of adequate insurance numerous times. The servicer would either ignore our client or their agents would request the same thing over and over.

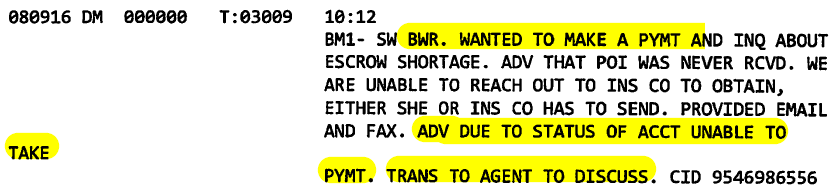

The evidence and testimony also established that our client repeatedly pleaded with the servicer to take her money. She tried to pay via their website but the system refused to let her log in. (She had logged in prior to them force-placing insurance without issue.) She also tried to make payments over the phone, but they refused to accept. There was an August 9, 2016 note in servicer’s comment log that states their representative advised our client, who was trying to pay by phone, that they were refusing to accept her payments.

Defense Trial Exhibit #1, Bates 000034.

On a side note, the purported default letter/opportunity to cure was dated on July 13th and gave our client until August 17th to cure. But for the servicer, not only would our client have remained current, she could have “cured” the problem they created. (Our client swore in her testimony at trial that she never got that letter and as detailed below, the servicer’s witness apparently committed perjury on the issue of whether the letter was even mailed.)

In September 2016, the comment log starts showing refunds and cancellations for forced-placed insurance. The servicer sent our client two letters, both dated September 14th, acknowledging that it canceled two different insurance policies. Still, one of those letters stated the servicer was charging our client $746.06 for “the time [their force-placed] policy was in force.” During this same time, the log also reveals that the servicer was contacting its attorneys, sending them documents and telling them who the named plaintiff for the case should be. In October, the servicer ran title searches and projected foreclosure and sale dates. Meanwhile, our client was continuing to call and e-mail, trying to resolve this and pay. She was told more than once by a particular servicer representative not to pay until the servicer fixed this. She kept trying anyway.

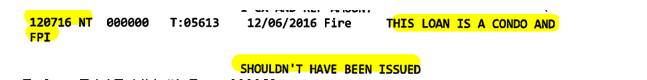

On December 7, 2016, the servicer’s log reveals:

Defense Trial Exhibit #1, Bates 000052.

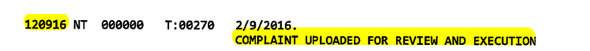

Despite this, two days later, the log also reveals:

Defense Trial Exhibit #1, Bates 000052.

So on December 7th, the servicer finally figured out that it wrongfully forced-placed insurance. Still, two days later it finalized preparing a lawsuit. Then, eleven days later, a bank (who my client had never dealt with before) and its servicer, filed suit to foreclose on our client’s home.

The bank and servicer could have easily fixed this situation numerous times. The prior servicer never had an issue getting proof of insurance. The condo association uses a company called “EOI Direct.” EOI stands for evidence of insurance. This company’s function was to make sure all lenders and servicers get evidence of insurance. The servicer here should never have forced-placed or overcharged our client in the first place. But when our client sent in the proof of insurance the day after the servicer wrongfully took too much money out of her checking account, it should have immediately remedied this. Instead, the servicer took approximately nine months to figure out that they wrongfully force-placed insurance. During that time, it refused payments and created a snowball of bogus charges. Then, after finally recognizing that it should never have done any of this, the servicer did not contact our client. It did not call or write. It did not credit the account, nor did it give our client a reinstatement quote. The bank and its servicer did not try to work this out in anyway. Instead, these financial institutions ran to the courthouse to try to take our client’s home.

Our client was served with the complaint during the day on new years’ eve 2016. She contacted our office in early January. We got in the case and asserted these critical affirmative defenses:

TENTH AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

UNCLEAN HANDS

Plaintiff’s claims are barred in whole or in part by the doctrine of unclean hands, equitable estoppel or both. Specifically, and without limitation, Plaintiff should not be permitted to obtain a judgment, foreclose or seek a deficiency judgment when it caused Defendant to “default” by improperly charging force-placed insurance on the subject property despite having knowledge that said the property was already covered by an adequate insurance policy. The defendant would have remained current but for Plaintiff’s improper charges.

ELEVENTH AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

UNCLEAN HANDS

Plaintiff’s claims are barred in whole or in part by the doctrine of unclean hands, equitable estoppel or both. Specifically, and without limitation, Plaintiff should not be permitted to obtain a judgment, foreclose or seek a deficiency judgment when it caused Defendant to “default” by improperly charging for force-placed insurance on the subject property. This insurance caused improper charges to accrue and caused Defendant to “default.” Despite having knowledge that said property was already covered by an adequate insurance policy and that the force-placed charges were improper, Plaintiff refused to credit the account and communicate to Defendant the amount needed for her to regain current status on the loan. But for these inequitable actions, Defendant would have remained current at all times.

TWELFTH AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSE

UNCLEAN HANDS

Plaintiff’s claims are barred in whole or in part by the defense of unclean hands. Specifically, and without limitation, Plaintiff should not be permitted to obtain judgment, foreclose or obtain a deficiency judgment as it informed Defendant, numerous times, not to pay. Defendant relied on those representations and eventually did as Plaintiff informed her to do. Yet, Plaintiff’s representations only harmed Defendant. Had Plaintiff not made those representations, Defendant would have remained current.

We prepared a proposed evidence chart and started issuing subpoenas for depositions. We ultimately subpoenaed and gathered evidence from the condo’s insurance agents and from our client’s bank. This showed adequate insurance was in place at all times. It also showed our client’s regularly and timely auto-payments. In all, there were 465 pages of insurance records and 682 pages of records from our client’s bank. This had to be studied, cataloged, tabbed, and redacted for filing.

In April of 2017, the servicer sent our client a check for $344.16, the exact amount of money improperly taken from her checking account in March of 2016. There was a memo on the check stub that states “FPI REFUND.” This check was issued four months after suit was filed and serves as additional evidence that the servicer, the bank and its lawyers knew they were proceeding with foreclosure, even though insurance was improperly forced-placed.

Of course, during all of this, our client was upset and confused about how this could happen. She is a genuinely nice person who really wanted to resolve this, pay, and move on with her life.

During the case, we filed two different motions for sanctions. One alleged that the bank knew or should have known that the facts and law did not support its case. Another motion for sanctions was the result of the bank not timely complying with a prior sanction order.

There were also numerous hearings due to the bank being evasive in its discovery responses. The bank and its servicer representatives even refused to sign interrogatory responses under penalty of perjury, like everyone else has to.

I think my comments just before I called our client to the stand at the October 30, 2018 trial best summarized Plaintiff’s discovery responses on the forced placed insurance issue:

Evan Rosen: The request for production was propounded on June 6, 2017. Number 19 says: Copies of all forced placed – this is requesting the production of copies of all forced placed insurance policies that have been ordered on defendant’s property from the inception of this account to the present date. After first giving us a response that was non-responsive, they eventually amended their response, the plaintiff, to assert that the answer to that on a March 16, 2018 response is none. There was, then, a response to interrogatory that was an amended response. Also, there were four motions to compel in this case. There is a sanction order for failure to comply, and there’s a pending motion for sanctions… So there is an amended interrogatory response to second set of interrogatories. Again, after multiple requests, they had said that there was no force-placed insurance. And then, when asked if insurance has ever been force placed on the subject property during the pendency of the subject loan, describe the relationship between any of the following entities: the owner of the loan, servicer and insurance carrier. [ ] — and this is the response from the plaintiff and their amended response, and this was from April 25th of this year, 2018. Response: Insurance was at one point placed on the loan account, which is the subject of the action — excuse me, of this action, in early 2016 [], the current loan servicer, detected there was a lapse in the insurance coverage. As a result of that, [] purchased a lender-placed hazard policy that increased borrower, []’s, loan payment. Subsequently, borrower, [], provided proof that she had insurance coverage that caused the current loan servicer, [], to issue two separate refunds to borrower, [], which as a result cleared and rectified the escrow account out completely with regard to the insurance-related aspect of the default at issue and returned it to just a default due to nonpayment of principal and interest.

October 30, 2018 Trial Transcript, P. L. – P. 75 L. 23.

The bank, its servicer, and their lawyers thought reversing the force-placed insurance six months after adding it, made everything just fine. But as the servicer’s September 2016 letter indicated, they were still charging our client a partial premium. And throughout the case, Plaintiff was claiming late fees and attorneys’ fees. Just before the date of the reconvened trial, they filed affidavits indicating they were seeking $24,788 in attorneys’ fees. Further, the evidence (testimony, e-mails, and comment log) all showed the servicer rejected her payments during and after all this was going on. We tried to resolve this numerous times but Plaintiff refused to remove the bogus charges and fees. Plus, after they filed suit, our client incurred attorneys’ fees and costs which the servicer refused to account for.

Prior to trial, I consulted with Jose Mitrani, a professor at FIU’s school of construction. I was exploring retaining an expert to opine on the replacement cost of the condominium so I could show the condo’s insurance coverage was always adequate. But I eventually decided not to pursue this. One, Plaintiff never raised an “avoidance” or sent any correspondence indicating they claimed the coverage was inadequate. And two, the condo rider in the mortgage contained strong wording that the condo’s coverage is almost always adequate.

In late October, trial prep kicked into high gear. I had to prepare the outline for our client’s direct examination, which included walking through numerous comment log entries while admitting into evidence various correspondence and documents to recreate a chronological history from when the servicer created this mess to the date of trial.

On October 30th, we showed up for trial in the morning but we had to wait until the afternoon to start. We got through Plaintiff’s case in chief, during which the bank’s witness likely committed perjury.

On direct, the witness claimed the servicer sent the breach letter. The bank’s lawyer, asked: “And who sent the breach latter?” October 19, 2019 Trial Transcript, P. 19 L. 17. And the witness responded, “[the servicer].” Id. at L. 18.

But later the witness completely changed her testimony:

Bank Lawyer: Are you familiar with [the servicer]’s practices for sending out breach letters?

Witness: Yes, I am.

Bank Lawyer: And what is that practice?

Witness: We use a third-party to send out our breach letters.

…..

We use a third-party to send out our breach letters.

October 30, 2018 Trial Transcript, P. 24 L. 18 – P. 25. L. 1.

As to verifying the prior servicer records for accuracy, to try to comply with the judicially created financial institution hearsay exception:

Bank Lawyer: Are you familiar with [the servicer’s] boarding process?

Witness: I am.

Bank lawyer: And what is that process?

Witness: Well, when we have loans that come over from prior servicers, they go through a boarding process where the information received is vetted into our system. It’s put into a trial mode to ensure that all of the needed items are there. And once it is verified for accuracy, if there are no issues, we board the item to a live file.

October 30, 2018 Trial Transcript, P. 8 L. 2-12.

Yet, on cross examination she stated otherwise:

Evan Rosen: If [the servicer] boards a loan and they check upon receipt that what’s shown in the prior servicer’s records are accurate, that the prior servicer’s records shows a payment was sent to [our client], how would [the servicer] know that that is accurate?

Witness: We would trust that if there’s a credit on prior servicer’s history that a credit was given.

…

Witness: We wait for the borrower to ask us about it, if there’s a discrepancy. … Witness: then the borrower would let us know there — well, because the borrower would say to [the servicer] there’s an error.

Evan Rosen: So you rely on the borrower to tell you if there’s an inaccuracy?

Witness: If we receive documents from a prior servicer with a credit on it, as you have proposed, we [accept] that prior servicer issued a credit. If a credit was not given, the only way [the servicer] would know would be for a borrower to say I never received that or for there to be some question come into play.

…

Evan Rosen: Of course, the same thing, [the servicer] is not looking at [the prior servicer’s] records to see if a check was actually sent for taxes, right?

Witness: We’re trusting the information that comes over from prior servicer.

October 30, 2018 Trial Transcript, P. 58 L. 11 – P. 59. L. 7.

Like in the above discovery admissions, the bank witness admitted at trial that insurance was improperly forced-placed: “Yes, there were escrow advances made for insurance, and those were found to be done in error, and that was corrected, and those advances were refunded.” October 30, 2018 Trial Transcript, P. 58 L. 8 – 11.

After the Plaintiff rested, our client was sworn. I read some discovery into the record, started into the direct examination, and admitted the comment log into evidence. But we adjourned early because the bank lawyer had a scheduling problem.

On February 18, 2019, trial reconvened. Our client took the stand. I tried to start by reading her opening testimony about the case from the prior transcript, but the judge told me I did not need to. He had complete notes and had already reviewed them. I then started walking our client through our well-thought-out direct examination. It was a chronology of events supported by the comment log, testimony, e-mails, and insurance declaration sheets. We also admitted all the condo’s insurance records that we obtained.

Our client covered how much this all affected her and how, but for the servicer, she would still be paying her loan and this case would not exist. She also covered how she did not get the breach letter and if she had, she would have paid. Based on the above critical comment log entry from August 9, 2016, her payment would have been rejected anyway. The amount on the letter was wrong to boot. The servicer added $9,000 for insurance charges. But the bank’s discovery responses and trial witness admitted that was added in error. Our client testified that she had continued to pay her taxes and condo dues throughout. She also said that if judgment was entered in her favor she would resume making her payments immediately. There was no reason she could not afford to do so.

To start my closing, I walked through some great quotes on the equitable doctrine of “unclean hands.” I reiterated the highlights from our client’s opening testimony while on direct examination in the first trial. I talked about the harm caused and that equity does what ought to be done. The court had to weigh the equities between foreclosing for the bank or entering judgment for our client. Taking her home was not what “ought to be done.”

The bank lawyer argued that they proved their case and our client just could not afford to pay. She then wrongfully claimed the comment log supported that our client could not afford the payments but did not point to a single entry that supported her argument. Because, there is no entry that supports this. In fact, there was no evidence whatsoever to support her argument. It was improper closing argument. I objected and raised this in my rebuttal. I also argued that if the bank wanted to rebut our affirmative defenses, they should have pleaded an avoidance and put on evidence in rebuttal to disprove it.

After leaning towards entering judgment for the bank, the judge started to come around after my rebuttal. He thought the fact that our client stopped trying to pay after suit was filed required him to rule for the bank. I explained that she had to hire a lawyer, and she could not afford to pay me and her mortgage. And, what reasonable person continues to try to make payments after all this. She tried many times via different methods. She was told several times, by the servicer representatives, not to pay. And her payments were rejected when she tried. They locked her out of her online account as well.

I also reminded him of the bank’s own comment log from August 2016 which evidenced the rejected payments. I asked him to take another look at it, which he did. And, after all this, the bank filed suit, added almost $25,000 in legal fees, more in costs, and is still trying to take her home. Who would continue sending payments to an entity that treated them this way? And more importantly, no reasonable financial institution should treat people like this. This was not the conduct of “honest and reasonable men.” Cong. Park Office Condos II, LLC v. First-Citizens Bank & Tr. Co., 105 So. 3d 602, 609 (Fla. 4th DCA 2013)(internal citations omitted). A court of equity must bar the relief Plaintiff seeks.

The judge finally saw the light and entered final judgment in our client’s favor. He specified that all payments through the date of trial were deemed paid and that the bank and servicer were required to accept all future payments.

Here is the final judgment: Final Judgment February 21, 2019

And a few months later, we helped our client recover every dime of the attorneys’ fees and costs that she paid during the case.